The purpose of understanding why enrollment in clinical trials is lower for AYA patients is because multiple studies have shown that patients who participate in clinical trials tend to have better outcomes.2,3 In addition, Potosky et al19 showed that AYA patients who were placed on clinical trials were more likely to receive appropriate therapy. From our systematic review, we found five studies that showed an association between better survival and clinical trial enrollment in the AYA population.2,11 Hence, it is important to understand the barriers to clinical trial enrollment of this population and to analyze the results of any previous interventions aimed at attempting to facilitate participation in clinical trials. Significant barriers to clinical trial enrollment discovered in this review included limited access and availability of clinical trials, as well as inadequate patient education, which will be detailed here.

A major reason why enrollment in clinical trials is poor for the AYA population is because of the lack of available trials. Shaw et al showed that from 2001 to 2006, a majority (57%) of AYAs aged 15–22 years at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh were not enrolled in a clinical trial because one was not available. This is compared with 41% of patients <15 years old who were not enrolled due to trial unavailability (P=0.04).14 This is partially because many clinical trials are designed with arbitrary age criteria that may not represent the biological age range of the disease being studied.12 In the UK, Fern et al found that only six of 49 clinical trials of cancers common in the AYA population had appropriate age criteria for this group.12

In addition to the limited availability of clinical trials to AYA patients, another related problem is reduced access to trials, which is determined at least partially by the referral patterns of primary care providers. Recent evidence suggests that most newly diagnosed oncology patients >15 years of age are being treated at community oncology facilities instead of NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers that typically offer the most clinical trials.15,16 Studies have shown that when referred to tertiary care centers, AYA patients are much more likely to enroll in clinical trials if treated by a pediatric oncologist rather than an adult oncologist.10 Yet, of adolescents with cancer treated in Ohio, only 36% of 17-year olds and 23% of 18-year olds were treated by pediatric oncologists compared with 76% of 15-year olds.17 Similar results have been reported in Utah and Georgia.16,18

While barriers to clinical trial enrollment are substantial, our review also yielded facilitators such as the formation of AYA centers and collaboration among large cooperative groups. One strategy used to improve enrollment in clinical trials for AYA patients has been the creation of AYA centers involving both adult and pediatric oncology departments. Shaw et al found that for the first 5 years after their joint AYA Oncology Program opened, clinical trial enrollment increased from 4% to 32%.20 Besides departments at individual institutions working more closely together, adult and pediatric national cooperative groups are now collaborating more to help enroll more AYA patients in clinical trials. For example, in 2000, the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG), which typically has only enrolled patients >18 years of age in clinical trials, opened a COG trial for metastatic Ewing sarcoma available to children and adults. Over the next 5 years, the number of sarcoma patients <40 years of age enrolled in clinical trials increased from 5.3% to 19.3%.21 Similar examples have been seen in the UK from 2005 to 2010, with enrollment increasing from 18% to 39% for 20-to 24-year-old sarcoma patients and from 6% to 35% for 15-to 19-year-old Hodgkin lymphoma patients.12

These improvements in clinical trial participation are likely due to large systems changes, which promote collaboration among providers and increase access for patients. For instance, within the last year, the NCI has changed their clinical trials system, forming the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN), which previously included nine adult cooperative groups, but now includes only four cooperative groups in addition to COG. The advantage of this system is that any provider who is a member of NCTN will have access to clinical trials from the other groups, and therefore improve trial availability.6 In the UK, the National Health Service created the National Cancer Research Networks in 2005, with the hope of improving recruitment for clinical trials. Through these regional networks, dedicated research nurses and data managers are able to assist providers in determining eligibility, managing informed consent, registering patients, and collecting data.22

However, although more trials are now available and accessible for AYA patients, providers and patients may still not be aware of this. Indeed, 62% of respondents in the AYA HOPE Study reported that they did not know whether clinical trials were available for their cancer type.13 NCI surveys of primary care providers revealed that 98% did not discuss clinical trials with patients of any age and 37% were not aware that clinical trials existed for their patients.23 Unpublished data from Gordon et al’s survey of primary care providers demonstrated that 78% of providers thought NCI-sponsored pediatric trials ended at age 21.24

DISCUSSION

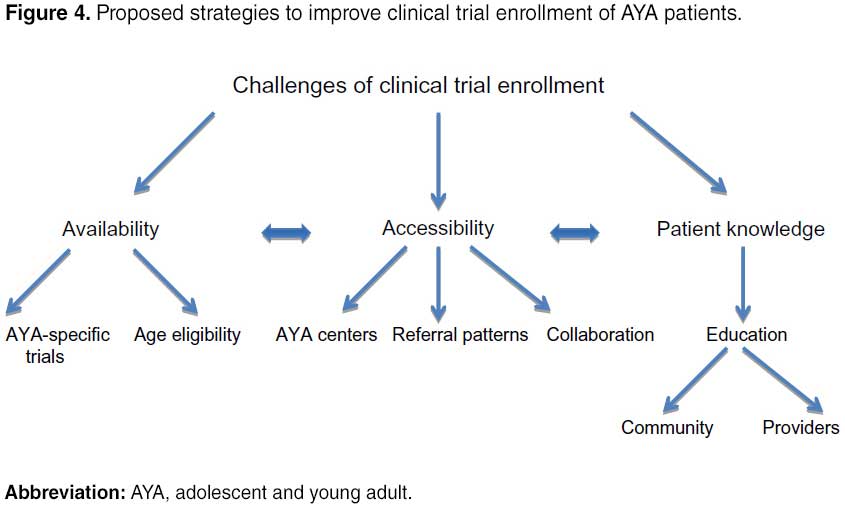

The results of our systematic review demonstrate that AYA patients continue to have low enrollment in clinical trials when compared with children and older adults. Reduced access, availability, and patient knowledge are major barriers to enrollment for this population.

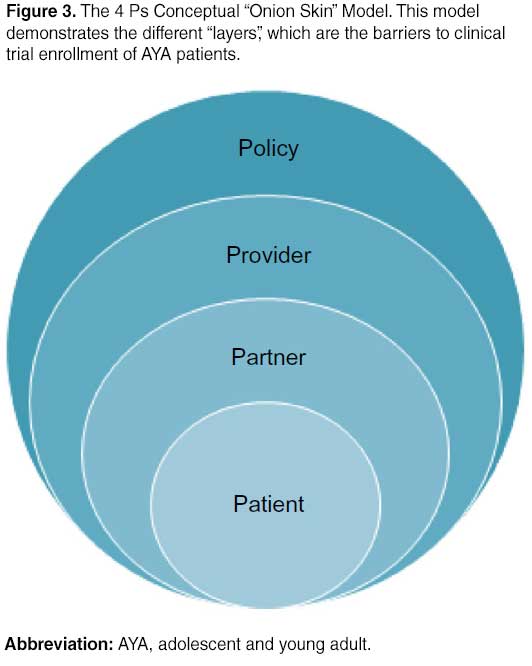

In order to address these barriers through specific interventions, we introduce the 4 Ps Conceptual “Onion Skin” Model (Figure 3). The idea is that there are multiple “layers” with barriers that relate directly to the patient’s ability to enroll in a clinical trial with the patient at the center. The “policy” layer is the closest to the surface but furthest from the patient as policy makers impact many patients yet their policies are not always aligned with the patients they serve. The layer closest to the center is the “partners” who are most closely related to the individual patient but not always the easiest to recognize. As we identify and target the problems related to these groups, we will be able to “peel” away the barriers to trial enrollment and hopefully this will lead to better patient outcomes.

This model originated with the idea that the care of AYA patients should be approached with the Donabedian model in mind. Through the 4 Ps, modifications can be made to the “structure” and “process” of recruiting AYA patients onto clinical trials and “outcomes” to these changes can be evaluated.30 Specific solutions will be discussed later and are outlined in Figure 4.