Small Batch: New kid-friendly cafe in Botanic Gardens serves build-your-own brunch boards

There’s a saying: Good things come in small packages — jewellery, gems, precious metals, and…food?

Well, there must be some truth to this adage, especially given the waves of miniature food trends online — something about watching mini donuts made with mini crockery in a mini fryer is so satisfying and leaves you hungry. (Am I the only one?)

On a similar note of tiny packages, Small Batch is a new, halal-certified concept with build-your-own brunch boards that come in bite-sized portions suitable for small humans and not-so-small humans, too.

It is the latest addition to The Black Hole Group’s dining concepts across Singapore, some of which you might be familiar with — Tipo Pasta Bar, The Great Mischief, Working Title, anyone?

It also serves up familiar Western classics along the likes of pastas, burgers, salads, sides and more — don’t worry, its offerings are not as miniature as the dollhouses or masak masak (play cooking sets) from your childhood!

Small Batch, launched recently in July, is located at the entrance of Jacob Ballas Children’s Garden, Asia’s largest garden dedicated to children. If you’ve never been, it is a space for kids to explore and learn about nature whilst having fun.

It’s no wonder the cafe has already drawn crowds of eager brunch-goers and families with young children.

Nestled among rich greenery, the cafe emulates modern farmhouse charm, with its wooden beams and warm, welcoming decor. It’s perfect for a cosy get-together or a quick pit stop after trekking through the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Although the cafe has an open-air concept, it’s well-equipped to keep you feeling cool and breezy even on the hottest summer day.

The menu at Small Batch

Foodwise, let’s see if good things do, indeed, come in small packages.

Small Batch’s signature brunch boards come with a choice of three items for S$15.90, five items for S$24.90 and S$4.90 for any additional add-ons. You can choose from six different categories to create the meal your heart desires — namely bakery, eggs, dairy, fruits and greens, protein, and treats.

Each category has its own share of options and we were definitely spoilt for choice — it’s almost as if we were at a buffet and didn’t know where to start! If you’re like us and you enjoy variety, we’d say its five-item brunch board is a good start.

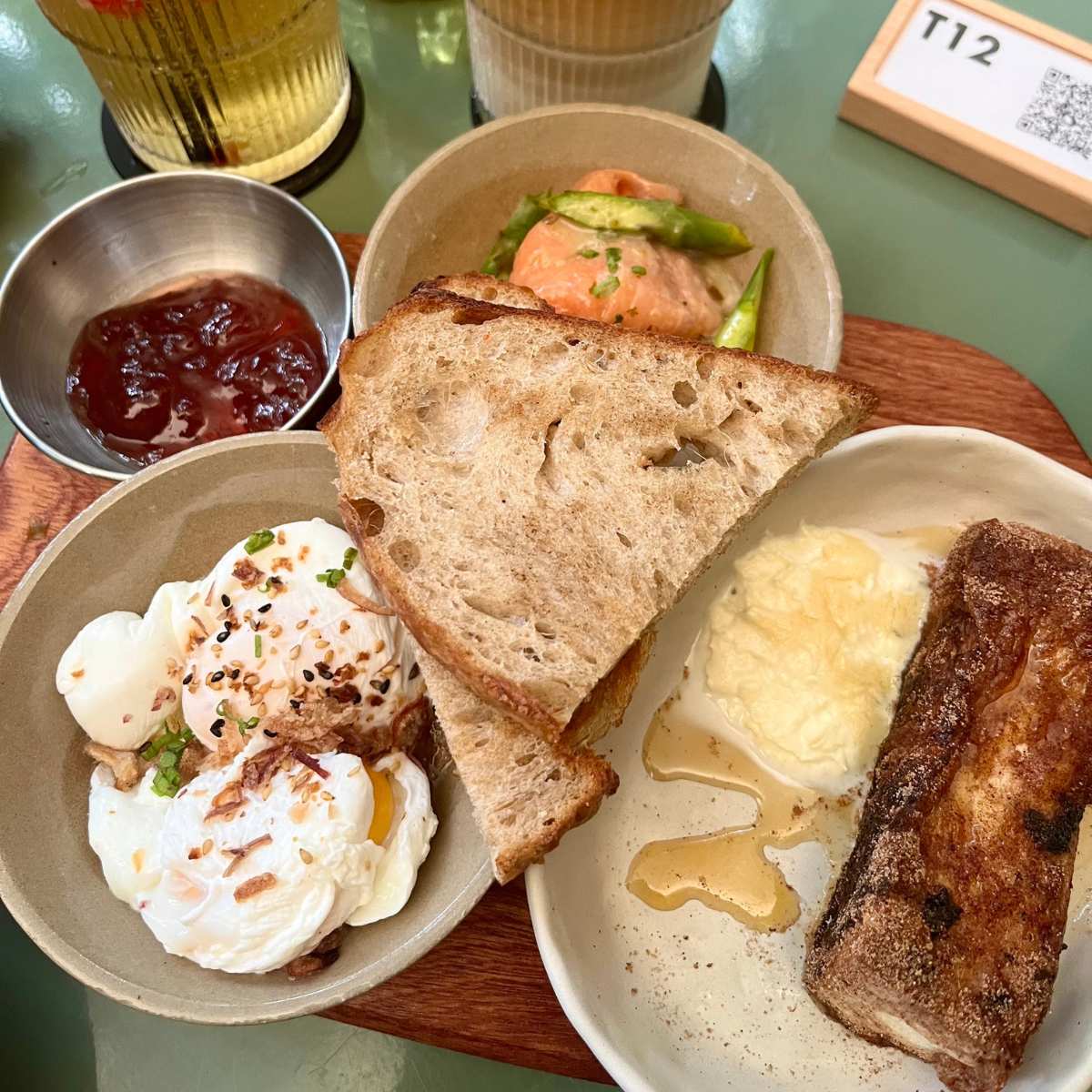

We ended up choosing an even spread — one item from each category, except dairy. This gave us two pieces of sourdough with a side of jam, poached eggs, smoked salmon, seasonal fruit salad, and French toast.

You could, however, go for multiple items from one category, if that’s what you like!

For all the items from the bakery section, you could choose to pair your chosen bake with butter, jam and olive oil and balsamic vinegar, or have it plain.

While it’s not a new concept to have customisable brunch or build-your-own brunch platters, what Small Batch does differently is in its plating. Each item is served in various individual bowls or plates (much like a buffet) and then stacked together on a wooden board. (How cute is that?!)

But, since the board could only fit so much, some items did end up being served separately.

The best thing about this brunch board, though, is you can eat it however you want — on its own or mixed together. It’ll be a satisfying meal either way.

We made ours into an open-faced sandwich: First a thin layer of jam on the sourdough bread, slapped on some smoked salmon and then finished it off with a perfectly runny poached egg right top, and voila! We completed our brunch board experience by having the French toast and seasonal fruit salad on its own.

Overall, we enjoyed the combination of our chosen brunch items — in particular, the smoked salmon came with asparagus and vinaigrette dressing, which undercut the sweet jam and the savouriness of the smoked meat and egg.

Because of how customisable the boards are, it’s a cinch to put together a hearty meal, whether it’s for an adult or a child. It’s also share-worthy, with multiple options to satisfy everyone’s taste buds.

For those who find the array of choices overwhelming, you could also opt for Small Batch’s classic cafe items such as its crispy fish burger (S$18) or beef bolognese rigatoni (S$18).

Small Batch’s kid’s menu

If your kid doesn’t fancy the brunch board, Small Batch also has a kids’ menu with a variety of items and portion sizes. As you would expect, it comes in smaller portions than items on the regular menu, though.

There’s also no shame here if you’re a grown adult looking for smaller portions — we should know, we got a meatball pasta (S$10) off the said menu.

We’d say the meatball pasta is a decent serving for kids under the age of 10, or if you find yourself wanting only two-thirds of your regular portions. The pasta has a reliable tomato-base, with savoury beef meatballs that give a great chew without being too tough — pure comfort in a bowl.

Not feeling up for a main course? Get a Kiddie bowl (S$8) — a small, palm-sized yoghurt bowl with fresh berries and honey. There’s also its fish sticks (S$10, crumbed fish fingers) or chicken fingers (S$10) — chicken fillets served with shoestring fries and garlic aioli.

Drinks-wise, Small Batch has options for refreshing sodas, fruit smoothies, cold pressed juices, and your usual coffee or tea.

We opted for its iced white (S$5.50) and its Smashed Strawberry Cooler (S$7), a refreshing concoction of fresh strawberries, lime, mint, honey and green tea. Be sure to stir it well to get your Insta-worthy shot of the swirling strawberries, but most importantly, for an evenly mixed sip of its slightly zesty, but sweet honey green tea.

If you’re planning to visit Small Batch, they currently accept reservations for weekdays only. As it’s relatively popular on the weekends, we recommend getting there early to beat the lunch crowd!

For more brunch eats, read about Cafe Manna, a brunch cafe in a chapel, or check out Summerhill’s brunch trolley buffet. Alternatively, check out the newest openings in Singapore here.

Do explore the GrabFood Dine Out service for awesome deals.

You can also book a ride to Small Batch at Botanic Gardens to try its brunch boards.

Small Batch

Singapore Botanic Gardens, Jacob Ballas Children’s Garden, 01-K1, 1H Cluny Road

Nearest MRT station: Botanic Gardens

Open: Tuesday to Friday (9am to 6pm), Saturday to Sunday (8am to 6pm)

Singapore Botanic Gardens, Jacob Ballas Children’s Garden, 01-K1, 1H Cluny Road

Nearest MRT station: Botanic Gardens

Open: Tuesday to Friday (9am to 6pm), Saturday to Sunday (8am to 6pm)