5 must-visit London restaurants for a whole day of eating

If you’re wondering what are some must-try food in London, check out these places for a well-rounded day of eating and feasting in the city. We’ve got you covered from brunch to after-dinner desserts.

1. Fish! Borough Market

Borough Market, Cathedral Street, London SE1 9AL

Opens: Mondays to Wednesdays (12pm to 10pm), Thursdays to Saturdays (12pm to 11pm)

Call it a cliche, but no trip to the UK is complete without fish and chips. Think fresh, battered fish fillets with a generous pile of hot chips.

We may be used to the Singaporean version of the same dish, which often comes with shoestring fries, fried till crispy and salted.

By contrast, chips from the UK are twice cooked, served without salt and are thickly cut. Diners are invited to sprinkle their own salt, alongside a healthy drizzle of vinegar, or whatever sauce they please.

I popped by on a weekday afternoon for a late lunch, and was met with a small crowd at its takeaway counter. This is to be expected, I suppose — according to its signage, its fish and chips is award-winning, and brought home prizes at the National Fish & Chips Awards.

Like most true-blue British chippies, Fish! offers a variety of fresh fish. There are seven to choose from, including more common ones such as cod and haddock, to ones I wouldn’t expect to see in fish and chips — skate and plaice.

What to order: Cod (£12.95 or S$21.54), halibut (£14.95), skate (market price)

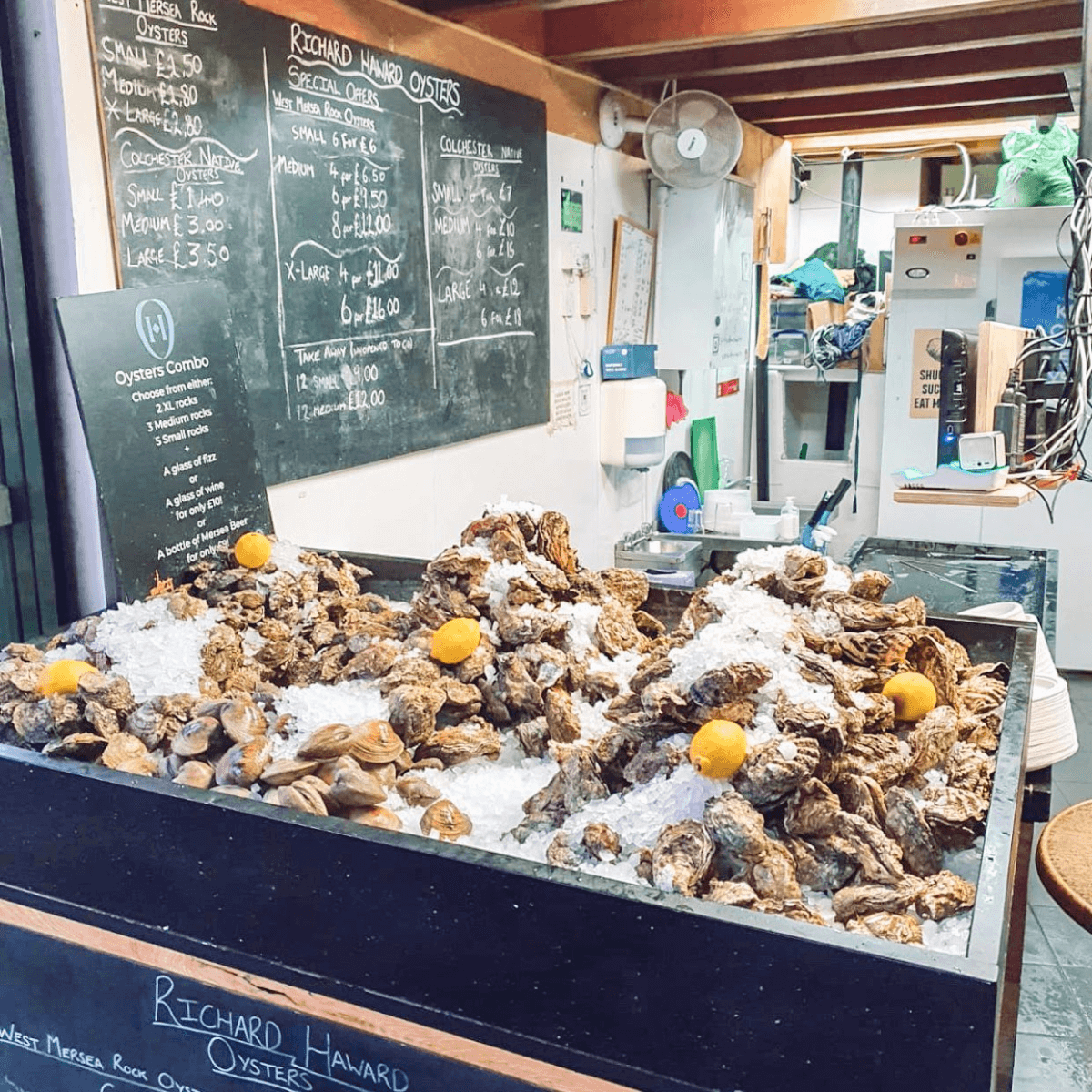

2. Richard Haward’s Oyster

35 Stoney Street, London SE1 9AA

Opens: Mondays to Fridays (10am to 5pm), Saturdays (8am to 5pm), Sundays (10am to 3pm)

Borough Market is a hotspot for visiting foodies, so it’s no wonder that this next eatery is also located within the same compound. You’ll never run out of choices when faced with the question of what to eat at Borough Market.

As its name suggests, this no-frills eatery serves up shellfish galore, with oysters taking much of the spotlight. Do note that only standing tables are available, and you may need to jostle with the queue for a comfortable spot to stand.

Check out the chalkboard behind the counter for the day’s catch and prices, or ask for a recommendation from helpful staff members.

The oysters are always fresh, carefully shucked and affordable. Add a dash of lemon, tabasco, or shallot vinegar sauce, as you please.

And since you’re on holiday, be sure to get a glass of bubbly to wash it all down.

What to order: Colchester native oysters (from £1.20), Mersea rock oysters (from £5 for six small pieces)

3. Fortnum & Masons’ Diamond Jubilee Tea Salon

Fortnum & Mason, 4th floor, 181 Piccadilly, London W1A 1ER

Opens: Mondays to Thursdays (11.30am to 8.30pm), Fridays to Saturdays (11am to 8.30pm), Sundays (11.30am to 7.30pm)

Now that you’re done with your midday meal, take an afternoon break for some quintessential tea and scones.

British tea brand Fortnum & Masons’ tea salon at its Piccadilly location is refined and elegant, with courteous wait staff to attend to your needs.

We do recommend booking in advance to secure your table, but you’re welcome to check in even if you do not.

Get the afternoon tea set for finger sandwiches, scones and pastries. The high tea, which includes savouries along the likes of Victoria lobster omelette with truffle, is a good option, too. Each set comes with a pot of Fortnum’s tea, with the option to top up for champagne cocktails.

Gluten-free and vegetarian options are also available.

What to order: Afternoon tea set (from £75 per person), high tea set (from £80 per person)

4. Dishoom

Multiple locations countrywide

Opens: Opening hours vary across locations

Dishoom was highly recommended by friends as a must-try. Dinner reservations are limited, so you may need to try your luck as a walk-in customer.

I visited its Shoreditch outlet on a weekday evening and was caught off guard by a queue that stretched at least 20 parties deep along the pavement outside.

It moved awfully quick, though, and the staff plied those waiting in line with piping-hot masala chai that tasted amazing — spicy, sweet and invigorating.

Once inside, the atmosphere was hopping and it was easy to see why the Indian restaurant is so well-loved.

Inspired by Bombay street food and Irani cafes of old, the two-storey restaurant is expansive, yet cosy, and outfitted with retro-style decor and tongue-in-cheek signage.

Foodwise, the curries are flavourful, albeit less spicy than what Singaporeans may be used to.

We recommend coming with friends, so you can order a larger variety to share.

What to order: House black daal (£8.50), Dishoom chicken tikka (£10.90), okra fries (£5.90)

5. Bilmonte

30 Windmill Street, London W1D 7LW

Opens: Mondays to Sundays (12pm to 12am)

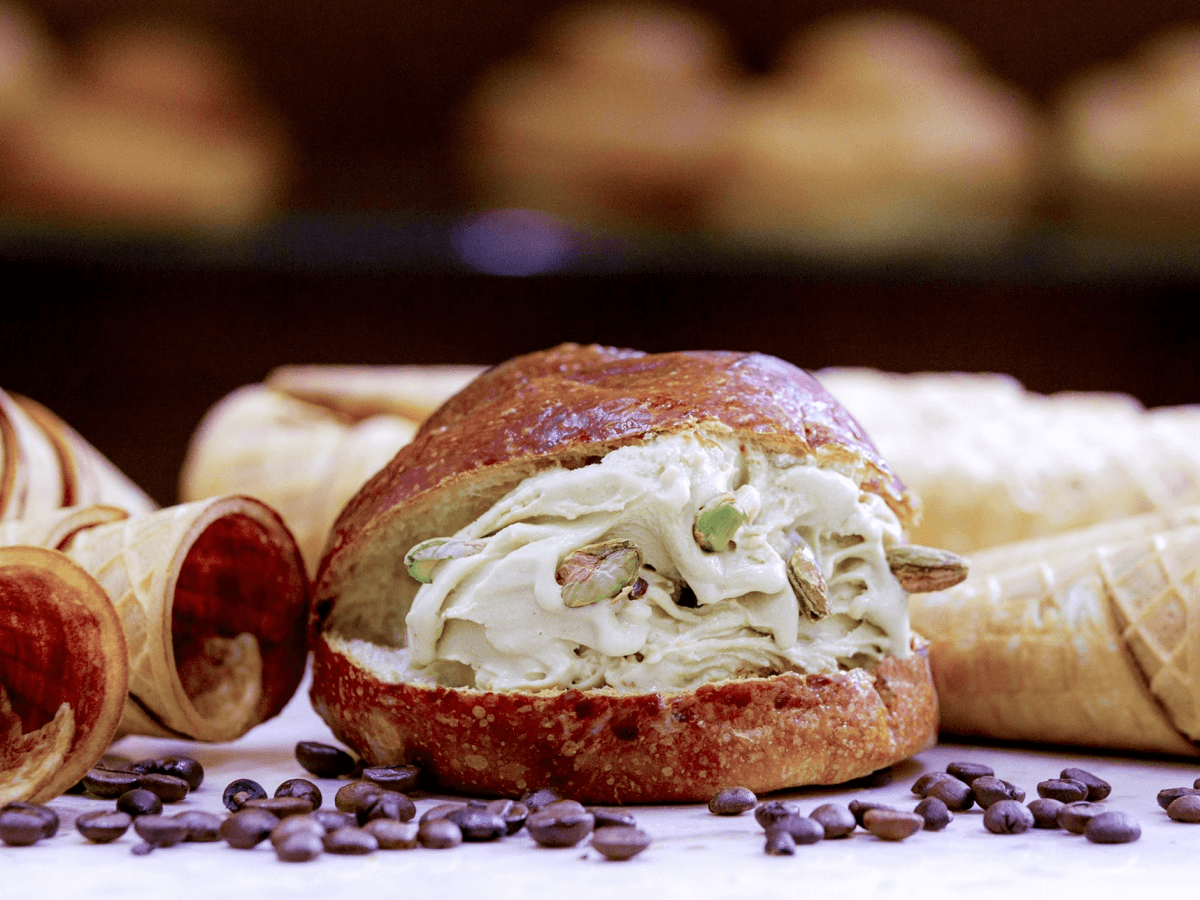

Take a short walk to Bilmonte gelateria in Soho, for a sweet treat to cap off that heavy meal.

This ice-cream joint is located in the heart of the city’s nightlife district, and seems a popular stop for many out for a night on the town.

Be sure to try its signature ice-cream bun — a scoop of Italian gelato ensconced within a warm brioche bun — with the option of being run under an ever-flowing tap of liquid chocolate fudge for that extra decadence.

What to order: Bun-brioscia (£8.50 with gelato, additional £5 with warm chocolate)